Delivering on the right to education in a punishing system

“When I got arrested, my number one concern was: what am I going to do with my education?”

Chris hoped he could get bail and continue his classes. Maybe he could get an ankle monitor and do them from home. But he didn’t get bail that week, or that semester. Chris was held in remand for more than two years.

“Remand” describes when someone is held in custody, after they have been arrested but before they have a trial. They have not been convicted of a crime but the court has determined that they should not be released while they await trial.

People held in remand have access to fewer programs and services than people who have been convicted and are serving a sentence, in part because remand was designed to be temporary. While that might be the intention, that is not the current reality.

In Chris’s case, he spent 26 months in remand before pleading guilty to the offence and starting to serve his sentence. By the time the court factored in credit for the time Chris served in remand, he had about one year of “sentence” left to serve. In other words, the majority of time Chris was incarcerated was spent in remand.

Ten months in, Chris spoke with Megan MacDonald, Education Program Director of Amadeusz, an organization that works with people who are incarcerated to further their high school and post-secondary education.

“In Canada, we see our education system as being really strong,” says Megan. “We think that everyone has a right to education – to free, accessible elementary and secondary school education. But a lot of people don’t think about this population. They’re behind walls. Their voices are not heard. They are forgotten.”

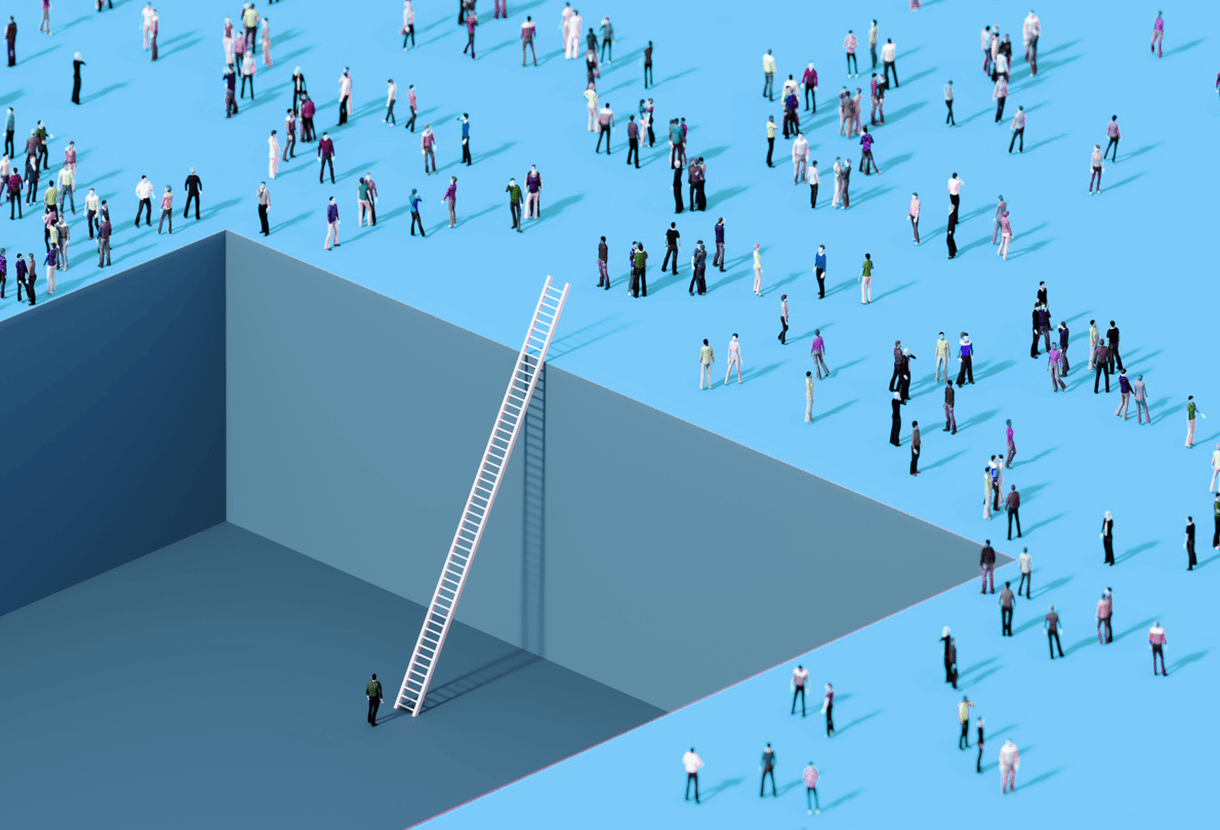

For people who are incarcerated, our society tends to see education as a privilege, rather than the human right that it is.

For Chris, doing college courses was a way of keeping himself focused on something constructive while waiting for his case to wind its way through the system. It was also a touchpoint with his previous life, in which education was a positive, driving force.

For Moka Dawkins, education on the inside was a welcome change from her experiences with school pre-incarceration. She grew up and went to school in Montreal, a racialized English-speaker in a French-language school system.

“The majority of my white teachers, they couldn’t understand me. I grew up in the Heights, and I spoke in slang. They weren’t really trying to understand what I was saying and where I was coming from, how I was trying to communicate.”

In addition to communication and cultural barriers, Moka sometimes found classes hard to follow, with so many other kids and everyone else’s questions confusing or distracting her. Her behavior sometimes landed her in trouble.

Moka was expelled from high school and moved to Ontario. At the time she entered incarceration, she had not completed her high school diploma. Through a social worker, she connected with Amadeusz and started working on her Ontario High School Equivalency Certificate.

With Amadeusz staff, Moka got the one-on-one support she didn’t in high school. “For example, when I was preparing for the exam, I would ask the guards to call to see if somebody was available. And someone would come and aid me. If I saw them in the morning, and I was still working on something, and I couldn’t get it, I would call for them again. Obviously, they had other people to see. But before they had to leave, they would come back to me. They were very supportive.”

That support was more than just academic. As a transwoman incarcerated in a men’s facility, Moka was often bunking in a cell alone. Amadeusz staff provided a vital social connection, some “girl talk” that helped her feel less alone, less misunderstood.

“It’s never just about education”

Many participants who enter Amadeusz’s program have had challenges with the public education system. Research indicates that three out of four people incarcerated in a federal institution have not completed high school, and more than half had less than a grade 10 education.

“A lot of people come into our program with this idea, ‘I don’t like education,’” Megan explains. Many feel the education system has failed them and don’t feel that education is a viable option for them. “Maybe they need extra support. Maybe they need flexibility because they’re also trying to work to support their family. There are all of these different things that the traditional education system doesn’t take into account.” In particular, many participants have had to focus on survival. Until your basic needs are met, it’s very difficult to make education a priority.

“There’s housing, there’s income, there’s family. It’s never just about education.”

Further, many participants have been “streamed” in the public education system, told what they should, or should not, strive for.

In contrast, Amadeusz’s approach centres on the needs and goals of the student. They provide individualized support to ensure that each student gets education that is relevant to their needs and goals. This could mean finding a path to college or university, or to a particular trade or career.

It also means taking into account the different life pressures that the students face. “We go in and they might tell us, ‘I’m trying to figure out how to get someone money so they can pay the rent.’ Even during incarceration, that stuff doesn’t just go away. So we ask, ‘Are you in the headspace right now to even focus on education?’”

Helping students succeed in a system designed to hold

The students are living in cells with one (or more) cellmates. In the cell are two beds and a small desk with two chairs. “In terms of a work area, you’re on your bunk – you could pull up your mattress and use the metal underside to write if you need to. If you want to go on the floor, I guess you could. I’d work on the desk,” explained Chris.

Moka would also look for a space outside her cell. “On a good day, when we’re unlocked the whole day, if it was quiet, I would do my schoolwork on the range, which is the common area,” she says. “They have this little office behind the guard’s desk. And sometimes when I wanted to be by myself, I would get permission from the guards to go in there and do my schoolwork.”

All courses available to participants are delivered on paper. Online courses are not an option. Students put pencil to paper, using textbooks and workbooks. They don’t have access to a physical or online library. “The main obstacle, by far, is the lack of accessible computers and internet,” Chris explains. “You can’t just google something. If someone from Amadeusz happens to be there, she can find an answer for you and get back to you. You can ask the officer, maybe they’ll be nice enough to look up something for you.” Otherwise, students are on their own. Amadeusz staff can act as a liaison between a professor and a student, who don’t communicate directly with each other.

During Chris’s time, the institution experienced multiple waves of COVID, and triple-bunking (in cells designed for two) was becoming more common. The judge determining Chris’s sentence gave him enhanced credit for the time he spent in remand, due to the abhorrent conditions he endured. Moka is part of a class action lawsuit based on living through a six-month guard strike, when people were “locked down with no showers, no phone calls – human rights violated.” During that time, Moka had no access to Amadeusz staff to talk to about her schoolwork, no chance of doing her exam and moving forward.

On the plus side, Moka points to the positive relationship she had with Amadeusz staff and the huge difference compared with her public school education. “The biggest advantage was the one-on-one support.”

The impact of that individualized, student-centred approach goes beyond diplomas and certificates. Megan explains that “Amadeusz is not just about getting people credits. It’s about trying to shift people’s view of education. For us, a huge win is when someone can say, ‘I never thought I could do this. Now I believe in myself. Now I’m looking forward to, what can I do next?”

Support for housing and employment would help people make a new start

After being released, both Chris and Moka have continued pursuing education. Chris did a certificate in social work, while Moka continued on to university. But, again, it’s never just about school.

When she was released, Moka stayed with a family friend. “The only option I had was to rely on them to help me with my parole and bail. I’m grateful for it.” However, Moka wishes she had the option to get her own apartment. “I was in a vulnerable situation. When you have to rely on someone – at any point, they could call 911 and say, ‘I’m tired of her.’” As she was continuing her transition with prescription hormones, she knew that the evolving expression of her gender identity would be challenging for the family she was living with. “I wish I had my own place to be comfortable with my self and not have to worry about suppressing certain aspects of my self, to appease somebody else, just to have a place to call home.”

The fast pace of life on the outside was also an adjustment. The family home was a bustling place, and changes in society were a lot to catch up to. For example, “when I went to jail, you could not talk to your remote. You could not tell your remote to turn on Amazon Prime. When I came out, everybody was talking to themselves! It gave me a little bit of paranoia when it came to the use of technology. I wish I had space to take in this little period in history that I missed and didn’t understand.”

Income was another challenge for Chris and Moka, both of whom received social assistance at some point after they were released. Social assistance doesn’t provide enough for basic living expenses, much less for tuition, school supplies, or other school expenses.

Looking for work when you have a criminal record is a challenge. “It’s like they want you to wear orange on the inside, and they want you to wear orange on the outside,” Chris says, referring to the low-paid, labour and construction jobs that likely won’t ask for a criminal record check.

He believes that a pipeline to job opportunities would be invaluable. It could be an internship, a mentorship program, or career training, with community partners that have experience working with people who have been incarcerated. Something that would give them an opportunity to show what they could contribute to an employer. “Just being given a chance, you know, ‘We see your value, we see your unique set of abilities.’ That act alone would be so important. Like ‘wow, someone cares and wants to see me do well. Let me not screw up this opportunity.’”

The positive benefits would reach beyond that individual, out into their communities. He explains, “If you gave a lot of these guys a full-time salary where they’re making just as much, or even a little bit less, than what they’re making on the streets – but they also know they’re not going to go to jail, they’re not risking life and limb – that stability would definitely reduce the number of people who are reoffending.”

The research bears this out. Despite the fact that employment is one of the most important protective factors that prevents people from reoffending, lack of guidance for employers on when it is appropriate to conduct record checks, and the stigma of incarceration make finding decent work very difficult for people post-release. The way the internet works now, any online mention of an offence can follow someone around for a lifetime. The unemployment rate among individuals recently released from incarceration is almost five times higher than that of the general population.

As with education, it feels like the odds are stacked against someone trying to make a new start by finding a good job.

“We can overcome these challenges”

Fortunately, Chris has been able to find work, with some help from a YMCA employment program. He’s working at a restaurant and a retail store; between the two, he’s working close to 40 hours, which gives him some stability and an income.

When Chris was arrested, he had just started his third year at York University. He was eyeing law school, or a Master’s degree, and a career in government or public office. By the time he left incarceration, he had graduated with a bachelor’s degree in political science and completed a college certificate in addictions counselling. His plan looks a little different now.

“I have 10 years until I can apply for a pardon. I need to stay out of trouble during that time. And I need to find something substantial, stable, and enriching during that period.”

Chris acknowledges that he lost time to “being stupid and making stupid decisions.” As a result, he is dealing with a new reality where more obstacles will stand in his way. But he insists that those obstacles are not insurmountable.

“There’s always going to be hope. We’re still alive, we’re still breathing, we’re still capable. You can always turn things around. It’s never too late. If you did time and you got out – you can make a living for yourself without going back to what you were doing that got you incarcerated in the first place.”

Meeting educational goals can be an important part of that. Amadeusz’s approach is to support each student as they take the lead, and make decisions that get them where they want to go. “Our participants are experts in their own lives,” says Megan. “We’re here to walk alongside them.” She observes that when students see what they can accomplish, their belief in themselves and their abilities grows – and with that their sense of potential and opportunity.

Moka is now a university student, a speaker, and an advocate for trans rights in prisons. She founded T-Time Tips, a non-profit organization that provides health and wellness advice for people who are BIPOC and trans. She wants to pursue a PhD in psychology, open a counselling practice, and continue being an entrepreneur.

“Nobody wants to go through a bad experience or trauma,” says Moka. “But when it does come across you at some point in your life, how do you move forward? You don’t hear too many stories of how people are surviving, especially of a racialized, transgender person. I’d never heard stories – the stories I hear are of murders, not of survivors.

“I want my voice heard. We can overcome these challenges. We can form a community around us that will support and uplift us. I don’t want people to feel like that’s not possible for them, because it really is.”